Mar 20, 2019

By Janet Thorngate, Chairman, SDB Council on History

People sleuthing their family history often discover that in the process of building that endless genealogy chart, the quest for illusive details draws them deeper and deeper into an ancestor’s world. Suddenly they are “into history” (though they never “liked history”) and the name on the chart becomes a real person.

As the names on the chart expand into biographical sketches, patterns emerge: ideas, attitudes, values. An identity. A culture. Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle wrote that history is the essence of innumerable biographies. If so, historians have much to offer genealogists and genealogists have much to offer historians.

Nothing illustrates these points better than two recent publications of the Rhode Island Genealogical Society, which also document many intersections with Seventh Day Baptist genealogy and history. The original plan of the co-authors was a new look at the life of John Crandall (1617/8-1675/6), a member of John Clarke’s Baptist church in Newport, Rhode Island. Happily, however, their ballooning research also spun off a full-length, very readable history book exploring John Clarke’s world.1 That world was also the world of Samuel Hubbard and all the first American Seventh Day Baptists, including, of course, Clarke’s nephew Joseph, who was key to the development of the Sabbatarian movement in Westerly and Hopkinton.

John Crandall’s Story

Like many early American immigrants, John Crandall was baptized as an infant into the Church of England and worked hard to help create a vastly different religious culture and society in New England. His descendants, many of whom were Seventh Day Baptists, benefited from his contributions to the fight for religious liberty and the formation of colonial government in Rhode Island. In a series of four articles in Rhode Island Roots (journal of the Rhode Island Genealogical Society), Judith Crandall Harbold and Cherry Fletcher Bamberg gather and greatly expand on what is known about John Crandall and his family while carefully disproving many “erroneous facts.”

Part 1 covers Crandall’s origins in Gloucestershire, England, noting that “the fanciful but persistent myth that John Crandall was the son of Sir John Crandall and Elizabeth Drake, a myth still alive and well on the Internet, has been put to rest.” Although little is known of his life between his ritual baptism in 1618 and his appearance in Newport in 1643, their description of how the “winds of religious change blew briskly through Gloucestershire” sets the stage for the contentious world of colonial religion and politics that welcomed him in the American colonies.

Part 2 describes attempts to document the still-unknown identity of Crandall’s first wife and his civic and church involvement in Newport as the Baptist church was evolving there. Well documented, however, is his part in the famous 1651 incident of Baptist persecution in Lynn, Massachusetts, which “seems to have changed him into an activist for Rhode Island and its toleration of religion.”

Part 3 chronicles the known facts about Crandall’s property and his years of public service, particularly his involvement in the struggle over the border between Rhode Island and Connecticut colonies and in the settlement of Misquamicut, incorporated in 1669 as Westerly. The authors portray the persistent conflicts between Rhode Island and its neighbors over land as extensions of the initial conflicts over freedom of religion. In this tumultuous world John Crandall became an important figure, one of two conservators (justices) of the peace for a large territory, representing Rhode Island law.

Focus in Part 4 is on Crandall as a husband and father of nine children, documenting what is known about each of them, verifying what is not known, correcting previously published errors, and, presenting it all in the form of a compiled genealogy (18 pages) with full documentation. Noting his complicated relationship to Seventh Day Baptists and the often-published error that John Crandall was a Sabbatarian, the authors express regret that, despite their “diligent efforts to find clues, the identity of John Crandall’s first wife, whom we know to have been a Sabbatarian, remains lost to history.” She was the mother of the first seven children, several of whom became Seventh Day Baptists. These included Peter Crandall, who donated the property in 1705/6 on which the first Seventh Day Baptist meetinghouse was built, and Joseph Crandall, the third pastor (elder) of the Newport SDB Church. It is only in a letter from his longtime friend Samuel Hubbard that John Crandall’s death is documented. It was while he was in Newport as a refugee in the middle of King Phillip’s War, the decisive early conflict between the English colonists and Native Americans. He died not knowing the outcome, whether Westerly, or even Rhode Island Colony, would survive.

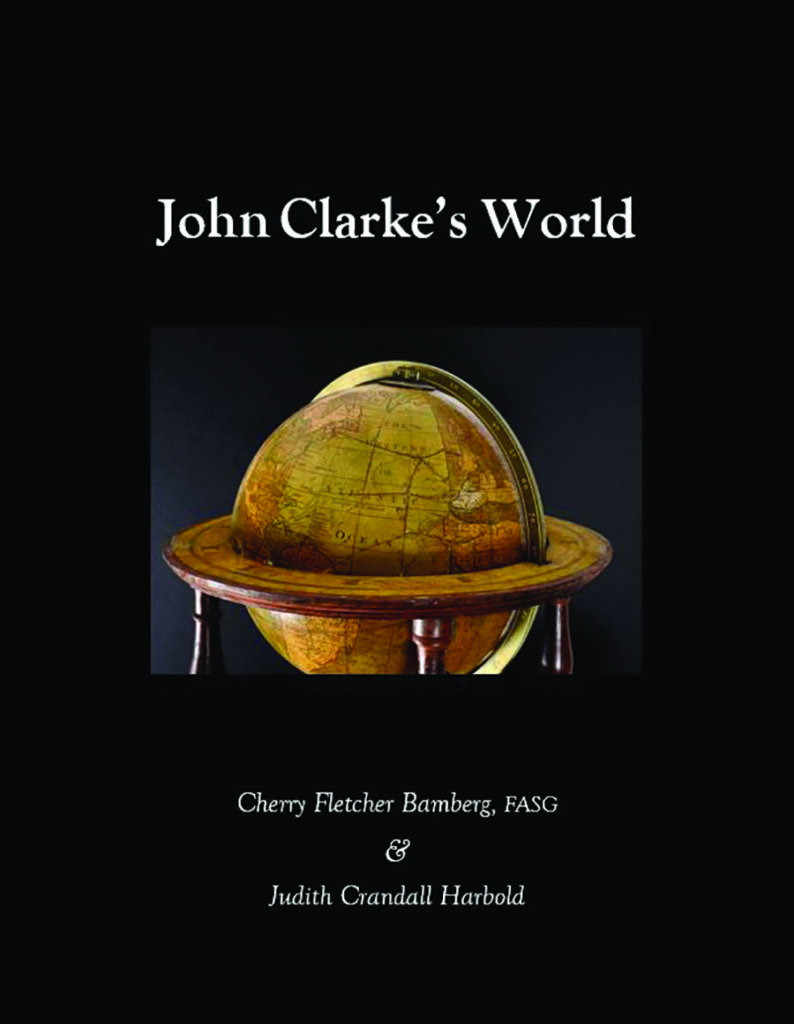

John Clarke’s World

John Clarke (1609-1676)—physician, Baptist preacher, colonial agent, one of the founders of Rhode Island. We cannot really grasp the significance of his life without stepping into his 17th century world, so different from our own. Authors Bamberg and Harbold tell “the story of Rhode Island’s founding and slow evolution into a unique place with a guarantee of religious liberty in relation to the people who lived through it, using their own words whenever possible.” One of the voices quoted liberally throughout is that of Samuel Hubbard, who, as a member of both churches, chronicled so much of what is known about the origins of John Clarke’s Baptist church and the Seventh Day Baptist Church that emerged from it.

John Clarke’s world was Samuel Hubbard’s world. They were born in nearby villages in Suffolk, northeast of London in East Anglia, Hubbard a year before Clarke. Suffolk was being “buffeted by winds of puritan controversy.” Both became part of the great migration from England to

Massachusetts Bay Colony and both experienced the religious persecution in its neighbor colonies that led to the founding of Rhode Island. Clarke was back in England securing the Charter of 1663 that guaranteed religious liberty for Rhode Island during the decade that Seventh Day Baptists were emerging there. He was back in Newport during the Sabbath controversy in his church and worked to implement the hard-won charter. Like John Crandall, he died as King Phillip’s War was devastating New England. Personal vignettes are sprinkled throughout the book.

A section on Samuel Hubbard provides no new biographical facts but certainly an enriching of the context, particularly the Suffolk years. Included are a picture of the church in Mendelsham (the town of his birth), a map locating his property in Newport, and a photograph of his gravestone, unearthed in 1988. The book provides a greatly expanded background and setting for Janet Thorngate’s Newport, Rhode Island, Seventh Day Baptists, which the authors frequently cite and to which they both contributed.

Bamberg and Harbold have distilled the essence of John Clarke’s biography. They do also include his genealogy—down through him and his seven siblings with new information on his three wives. The ten children of his brother Joseph (1618-1694) are listed. John himself had no biological descendants, yet a legacy.

Concluding sentences highlight the symbiotic relationship between genealogy and history: “Roger Williams, John Clarke, Obadiah Holmes, John Crandall, Samuel Hubbard, their wives, and their friends had all come to Rhode Island ‘on the wing’”…The legacy of these stalwart men and women survives in the Baptist and Sabbatarian churches of the present and in America’s commitment to freedom of religion. In a certain sense, whether or not we carry their DNA, all Americans are descendants of John Clarke and his companions.”

About the authors:

Cherry Fletcher Bamberg, FASG, has been editor of Rhode Island

Roots, quarterly journal of the Rhode Island Genealogical Society, since 2002. As a fellow of the American Society of Genealogists, her long list of publications is on their website (fasg.org).

Judith Crandall Harbold, RN, BS, MA, is President of the Crandall

Family Association. Her family history interest has led to articles on early Rhode Island, especially the descendants of her immigrant ancestor John Crandall.

1 Cherry Fletcher Bamberg FASG and Judith Crandall Harbold, John Clarke’s World (Hope, RI: Rhode Island Genealogical Society), 2018. 10×7, hardcover, dustjacket, 462+xxxiv pages. Illustrations, genealogical charts, maps, bibliography, index. ISBN 978-0-9827665-4-5.

The book can be ordered from Rhode Island Genealogical Society (RIGS), P.O. Box 211, Hope, RI 02831 or at RIGenSoc.org, for $50.

2 John Crandall’s Story by Judith Crandall Harbold and Cherry Fletcher Bamberg FASG, is published in these four 2018 and 2019 issues of Rhode Island Roots:

“Waterleigh to Rhode Island,” Vol. 44, No. 1 (March 2018), 2-16.

“John Crandall (Part Two): Stepping Forward,” Vol. 44, No. 2 (June 2018), 87-109.

“John Crandall (Part Three),” Vol. 44, No. 3 (September 2018), 129-147.

“John Crandall’s Family (Conclusion of Series),” Vol. 45, No. 1 (March 2019), 18-47.

Back copies of Rhode Island Roots can be obtained several ways: Rhode Island Genealogical Society (RIGS) members can view pdfs on the website RIGenSoc.org. Anyone can order paper or pdf copies from RIGS, P.O. Box 211, Hope, RI 02831 or at RIGenSoc.org for $3.50 postpaid. Issues older than five years can be read at the New England Historic Genealogical Society website AmericanAncestors.org. RIGS membership for $25 includes a full subscription plus other benefits; see RIGenSoc.org.