Jan 23, 2018

First in a series of spinoff articles from recent research on the Newport, Rhode Island, Seventh Day Baptists

by Janet Thorngate

Most people who have even a smattering of American Seventh Day Baptist history know that the first Seventh Day Baptist church in America was founded in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1671 and that Samuel and Tacy Hubbard and their daughter Rachael Langworthy were three of the seven charter members. And anyone who has visited the Seventh Day Baptist museum in the last 100 years has seen the oldest book in our archives, the “Hubbard Bible,” of which Hubbard said, “Now 1675 I have a testament of my grandfather Cooke’s printed 1549, which he hid in his bed-straw lest it should be found and burnt in queen Mary’s days.” Those who have studied the history to any extent know that we would know little about the origins of the church and its first twenty-one years were it not for the extensive writings of Samuel Hubbard.

So, what is new? What emerges from recent research into the wider context of the seven places Hubbard lived before arriving in Newport at age thirty-eight? We find that he viewed his life as a pilgrimage, each new beginning growing from earlier roots. What emerges from closer examination of his writing is the strong force of family nurture as it influences a growing church. The courage to follow one’s conscience wherever it leads gathers strength from both of these themes.

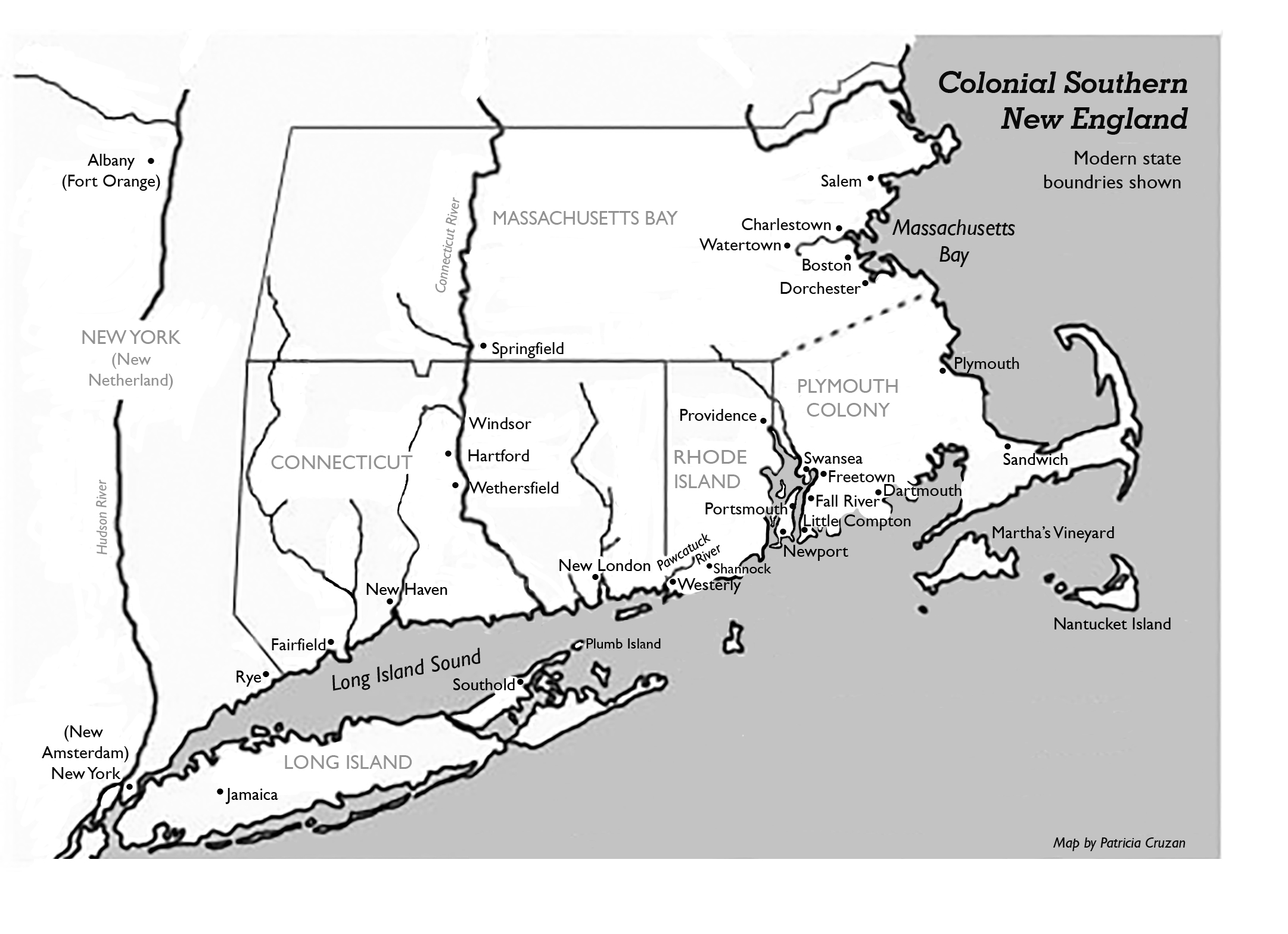

Samuel Hubbard grew up in Mendelsham, Suffolk, England, an area known for religious dissent. He was aware that grandparents on both sides had suffered persecution for their faith, and he described his own Christian conversion at age sixteen as influenced particularly by his mother’s seeing to it that he heard “choice ministers.” It was apparently with older siblings that he joined the migration to Massachusetts Bay Colony at age twenty-three. Here he became acquainted with Roger Williams, whose radical opposition to the conscience-stifling practices of the Standing Order Congregational Church had not yet caused his banishment to what became Rhode Island. Hubbard’s own journey took him further and further away from the long arm of strict Puritan Boston to new frontiers.

First Hubbard moved west to Watertown where he was accepted in the Standing Order Church “by giving account of my faith,” but he shortly joined a migration south along the Connecticut River to form new settlements near what became Hartford. In Windsor he married Tacy Cooper during the harsh winter that sent most of the sixty settlers back to Massachusetts. After a short move north to Wethersfield, where their first two children died, they settled in Springfield, a fur-trading post at the intersection of several Indian trails. Here were born the three daughters who survived: Ruth (later Burdick), Rachael (later Langworthy), and Bethiah (later Clarke). Here Samuel was involved in establishment of the town church, again “giving account of my faith” along with four other male members, “my wife soon after added.”

After nine years, however, Massachusetts Bay Colony passed a law against Baptists (anyone opposed to infant baptism) and Springfield was now on the contested border between Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut colonies. The Hubbards suddenly moved down the full navigable length of the Connecticut River to Long Island Sound and west to the far edge of the colony near the New York border. It was not far enough. When Tacy zealously made known that she believed in baptism only of people who had clearly expressed their own adult belief, and Samuel “was also said to be as bad as she,” they were given the option of prison or banishment. Thus, after only five months in Fairfield, Connecticut, they “went for Rhode Island.” It took them twelve days to go the 125 miles to Newport where they were immediately baptized by John Clarke and joined the Baptist Church. Ruth was eight, Rachel six, and Bethia two, their parents not yet forty.

For the next twenty-four years Hubbard was an active layman in the Newport Baptist Church. His “gift of prophesying publicly in the church” was encouraged, and he was often sent to represent the church among new contacts or persecuted Baptists in neighboring colonies. The daughters, baptized as young women, married and began families. The Hubbard farm (Maidford), where he also conducted his carpentry trade, was near that of John Clarke and other members on the northern edge of Newport near the center of the island.

Then, as all good American Seventh Day Baptists know, came Ann and Stephen Mumford to Newport calling attention to the seventh-day Sabbath of Scripture. They had been two of several Sabbathkeeping members of the Baptist congregation in Tewkesbury, England. First Tacy Hubbard, and within two years eleven other members of the Baptist church, began observing the seventh-day Sabbath. These included daughters Ruth and Bethiah and Bethiah’s husband Joseph Clarke (nephew of John Clarke) who were already among the first settlers on the Rhode Island frontier in Westerly (now Hopkinton). Thus, keeping the seventh-day Sabbath began almost simultaneously in two Rhode Island locations, a day-long trip apart by boat and footpath or horse trail.

Map of Colonial Southern New England showing towns where the Hubbards lived or visited other contacts and church members.

During the seven years after the Mumfords’ arrival in 1664, while the Baptist church struggled to accommodate differences in practice, the young William Hiscox emerged as the capable leader and spokesman for the Sabbatarians. Hubbard, recording the controversy in his “Register” and copying the voluminous correspondence between Sabbatarians in Old and New England, rejoiced in the Biblical preaching and debating of “brother Hiscox.” He would become the son the Hubbards lost. Their first son, Samuel, was born and died as a child in Springfield; the second Samuel, born in Newport, died of smallpox at age 21, one year before the Seventh Day Baptist Church was organized. In reflecting on progress of the church thirteen years later, Hubbard declared, “Jehovah hath made this bud or branch to grow to a tree by adding Brother Hiscox: wonderful grace.”

The family tree and the extending church family tree grew from a firmly rooted covenant. Through it they were “seeking God’s face among ourselves for the Lord to direct us in a right way for us and our children.” They “entered into covenant with ye Lord and with one another and gave up ourselves to God and one to another” with a “sense upon our hearts of great need to be watchful over one other…edifying and building up one another in our most holy faith.” The strong arms of the covenant embraced those first baptized—a full day’s boat trip west in New London, Connecticut—and called far-flung members back for yearly meeting from even further east in Plymouth Colony and Martha’s Vinyard. For thirty-seven years the covenant nurtured the first daughter church not set off until 1708 (I Hopkinton) but still considered “a sister church in covenant relation with us.”

Samuel and Tacy’s journey was a shared one. In a 1688 letter he wrote:

Thro’ God’s great mercy the Lord have given me in this wilderness a good, diligent, careful, painful [painstaking] & very loving wife: we thro’ mercy live comfortably, praised be God, as coheirs together, of one mind in the Lord, travelling thro’ this wilderness to our heavenly Sion, knowing we are pilgrims as our fathers were; & good portion being content therewith.

He was quick to acknowledge his wife’s leadership at crucial points in the family pilgrimage: first to proclaim Baptist views, first to begin keeping the seventh-day Sabbath, first to proclaim to the Baptist church the “grounds” on which the five based their decision to withdraw.

In 1686 when they had been married fifty years, Samuel 76 and Tacy 78, they “counted up” how long each had been “a convert, an independent [Congregational] and joined to a church, a Baptist, and a Sabbathkeeper,” concluding, “We are by rich grace born up & adorned with rich mercies above many, as to have all my three daughters in the same faith & order, & 2 of their husbands, and 2 of my grand daughters and their husbands also with us. O Praise the Lord, for his goodness endures forever!” The Hubbards’ joy seemed rooted in their concern that the faith of the next generation have the vitality to continue “the same faith and order.” In this same letter he wrote, “This church in general is reasonable well, & of late, in great unity, praise be to God.”

Two years later, in 1688, they erected their Ebenezer (a stone commemorating God’s presence and help—I Samuel 7:12-14) in a family burial place on the farm. It listed their names and those of the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Samuel apparently died later that year although when his gravestone was found in a nearby flower bed 300 years later, the death date was unreadable. Tacy lived at least another nine years to age 88 when the church minutes record that she and one other member voted against a specific disciplinary action and the church suspended the matter.

Generations of Hubbard spiritual descendants, not to mention the large percentage of their biological ones, continue “coheirs together, of one mind in the Lord” three hundred and fifty years later. We do well to be “knowing we are pilgrims as our fathers were.”

________________

Sources for all the information in this article may be found in Baptists in Early North America: Newport, Rhode Island, Seventh Day Baptists by Janet Thorngate (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2017). In addition to a history of the church in its historical context, the book includes the previously unpublished church records and the collected writings of Samuel Hubbard pertinent to the church’s history. The book may be ordered from the publisher for $60: www.mupress.org or Mercer University Press, 501 Mercer Univ. Dr., Macon GA 31207.

Samuel Hubbard’s gravestone is currently in Paradise School, museum of the Middletown Historical Society, about five miles north of downtown Newport. It was found 30 years ago in a flower bed a little further up the Maidford River at Whitehall Museum House, the 1729 home of Anglican Bishop George Berkeley, maintained since 1899 by the Society of Colonial Dames. Berkeley’s 96-acre farm, now a residential area, apparently included what had been Samuel Hubbard’s 25-acre farm where the Sabbatarians met for worship at least as early as 1669. There, about 100 years later, in 1763, Congregational minister Ezra Stiles found the Hubbard’s Ebenezer stone and transcribed it.